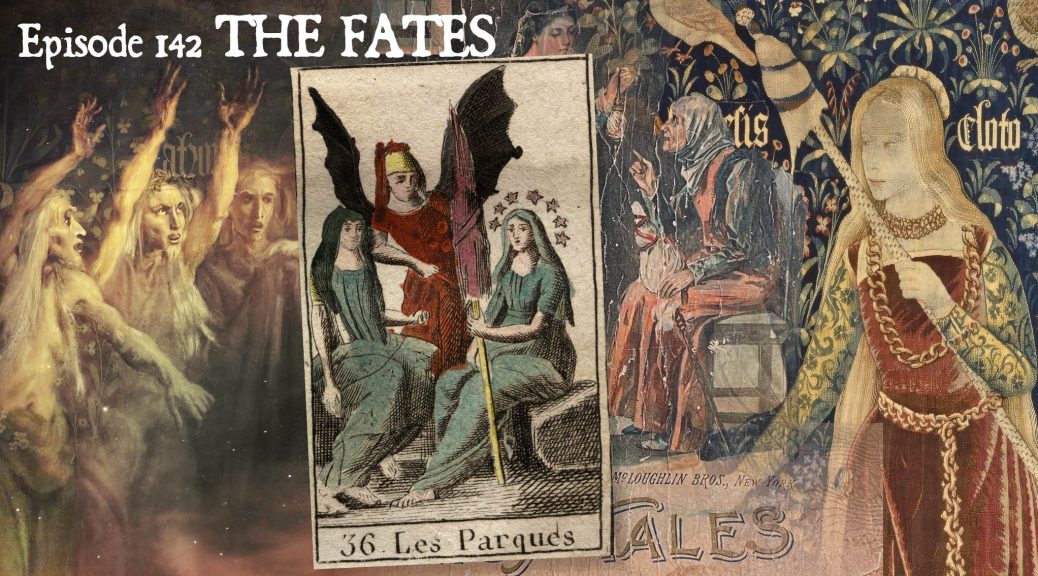

The Fates

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 49:48 — 57.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

The Fates of Classical Antiquity not only survived in the form of related fairy-tale figures but also as the object of superstitions and rituals associated with newborns. In South Slavic and Balkan regions particularly, these customs represent a surprisingly long-lived and genuine case of pagan survival.

We begin our episode examining the fairy godmothers of “Sleeping Beauty” as embodiments of the Fates. Mrs. Karswell reads a few key passages from the definitive version of the story included in Charles Perrault’s 1697 collection, Histoires ou contes du temps passé (“stories of times gone by.”) We learn how the fairies fulfill the historical role of godparents at the newborn’s christening. We also note the peculiar emphasis on the quality of what’s set before the fairies at the christening banquet, observing how a failure there leads the wicked fairy to curse the Sleeping Beauty.

We then explore antecedents to Perrault’s tale, beginning with the 14th-century French chivalric romance, Perceforest. A peripheral story in this 8-volume work is that of Troylus and Zeelandine, in which the role of Sleeping Beauty’s fairy godmothers are played by Greek and Roman deities, with Venus as supporter of Princess Zeelandine (and her suitor Troylus) and Themis cursing Zeelandine to sleep in a manner similar to Perrault’s princess. A failure to correctly lay out Themis’ required items at the christening banquet is again again responsible for the curse, though the awakening of Zeelandine by Troylus awakens is surprisingly different and a notorious example of medieval bawdiness.

Preceding Perceforest, there was the late 13th-century French historical romance Huon of Bordeaux, in which we hear of the newborn fairy king Oberon being both cursed and blessed by fairies attending his birth. From around the same time, French poet and composer Adam de la Halle’s Play of the Bower describes a banquet at which fairy guests pronounce a curses and blessings on those in attendance prompted again by their pleasure or displeasure at what’s set before them at a banquet. We also hear of the Danish King King Fridlevus (Fridlef II) bringing his newborn son to a temple of “three maidens” to ascertain the destiny pf the child in Gesta Danorum (“Deeds of the Danes”).written around 1200 by Saxo Grammaticus. And lest listeners think such appeals to the Fates were strictly a literary motif, we hear Burchard of Worms, in his early-11th-century Decretum, condemning the not uncommon among the Germans of his region of setting up offering tables for the Fates. By this point, the connection between how fairy godmother types are served at a banquet and offerings made to the Fates to ensure a cild’s fortune should be clear.

We then turn back to the Greek Fates, the Moirai (Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos) and the Roman Parcae (Nona, Decuma, and Morta). Particularly in the case of the Parcae, we hear examples of their connection to the newborn’s destiny in the celebration nine or ten days after the birth of the dies lustricus, during which offerings were made to the Fates.

We make a brief side-trip to discuss the Norns (Urðr, Verðandi and Skuld), the Germanic equivalent of the Fates. These are more distant cousins, not strongly associated with the newborn and his destiny, though we do hear a passage from the Poetic Edda, in which the Norns are present birth of the hero Helgi. We also hear a gruesome passage from the 13th-century Njáls Saga, in which the Valkyries weave out the fate of those who will die in the Battle of Clontarf.

The Anglo-Saxon equivalent of the Fates, the Wyrds, are also discussed, and we hear how the witches in Macbeth partook in this identity as the “Weird Sisters,” an association Shakespeare inherited from his source material, the 1587 history of Great Britain, known as Holinshed’s Chronicles.

We then turn our attention the Fates in Slavic and Balkan lands — the Rozhanitsy in Russia and Ukraine, the Sudičky among West Slavs, the Orisnici in Bulgaria, and the Ursitoare in Romania. As these customs survived into more recent times, there is a vast body of folklore to describe — much of it revolving around the setting up of offering tables and the communication of newborn’s destiny through dreams sent to mothers and midwives and confirmed by marks (visible or invisible) left upon the infant during their nocturnal visits on the third night after birth.

We also enjoy a couple entertaining folktales about Romania’s Ursitoare collected in the early years of the 20th century by folklorist Tudor Pamfile.

While such customs have since died out in Greece, customs related to the Moirai preserved into the early 20th century, as we hear in passages of John Lawson’s Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion: A Study in Survivals, written in 1900.

We end with a brief look at christening parties in modern Romania, at which costumed Ursitoare play an increasingly major role, this paired with an introduction to the popular song “Ursitoare, Ursitoare.”