Rolling Hells and Land-Ships

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 33:35 — 38.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

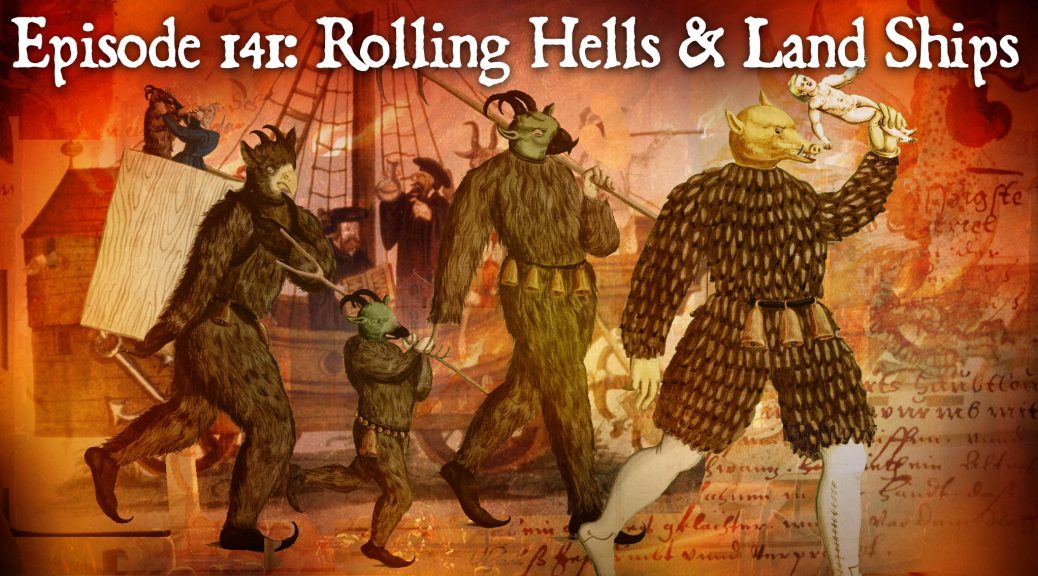

During the 15th-century, citizens of Nuremberg, Germany, experienced spectacular Carnival parades highlighted by the appearance of floats known as “hells.” Featuring immense figures, including dragons, ogres, and man-eating giants, these hells were also peopled with costumed performers and enhanced with mechanized effects and pyrotechnics.

In this episode, adapted from a chapter of Mr. Ridenour’s new book, A Season of Madness: Fools, Monsters and Marvels of the Old-World Carnival, we examine the Nuremberg parade, the Schembartlauf, as it evolves from costumed dance performances staged by the local Butcher’s Guild in the mid-1 4th-century into a procession of fantastic and elaborately costumed figures, and finally — in 1475 – into a showcase for the rolling hells.

We begin, however, with an examination of a historical anecdotes sometimes presented as forerunners of the Carnival parades, and of the Schembartlauf in particular, including two sometimes put forward to support a “pagan survival” theory. The first involves a ceremonial wagon housing a figure of the putative fertility goddess, Nerthus, hauled about by Germanic peoples in the first century and mentioned in Tacitus’ Germania. The second, also involving a wagon with fertility figure, is described by Gregory of Tours as being hauled through farmers’ fields in the 6th-century.

A third case involves the mysterious “land-ship,” a full-scale wheeled ship hauled from Germany into Belgium, and the Netherlands in 1135. Mentioned exclusively by the Flemish abbot, composer, and chronicler Rudolf of St. Trond in his Gesta Abbatum Trudonensium (Deeds of the Abbots of Trond), it’s characterized by the abbot as a sort of pagan temple on wheels and locus of orgiastic behavior, the precise purpose and nature of this peculiar incident remains largely a mystery.

We then hear a comic incident imagined in the early 13th-century story of the knight Parzival as told by Wolfram von Eschenbach. By way of analogy to the character’s ludicrous behavior, Carnival is mentioned for the first time, or more specifically von Eschenbach use the German word for Carnival, specifically the Carnival of Germany’s southwest called “Fastnacht.”

Our story of the Schembartlauf concludes the show with a description of its ironic downfall through local intrigues fired by the Protestant Reformation. Worth mentioning also, in our Schembart segment, is the heated scholarly debate around objects depicted in period illustrations, which look for all the world like oversized pyrotechnic artichokes.

New Patreon rewards related to Mr. Ridenour’s Carnival book are also announced in this episode, along with related Carnival-themed merch in our Etsy shop, including our “Party Like it’s 1598” shirts featuring Schembart figures.