St. George, the Dragon, and More

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 49:16 — 56.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

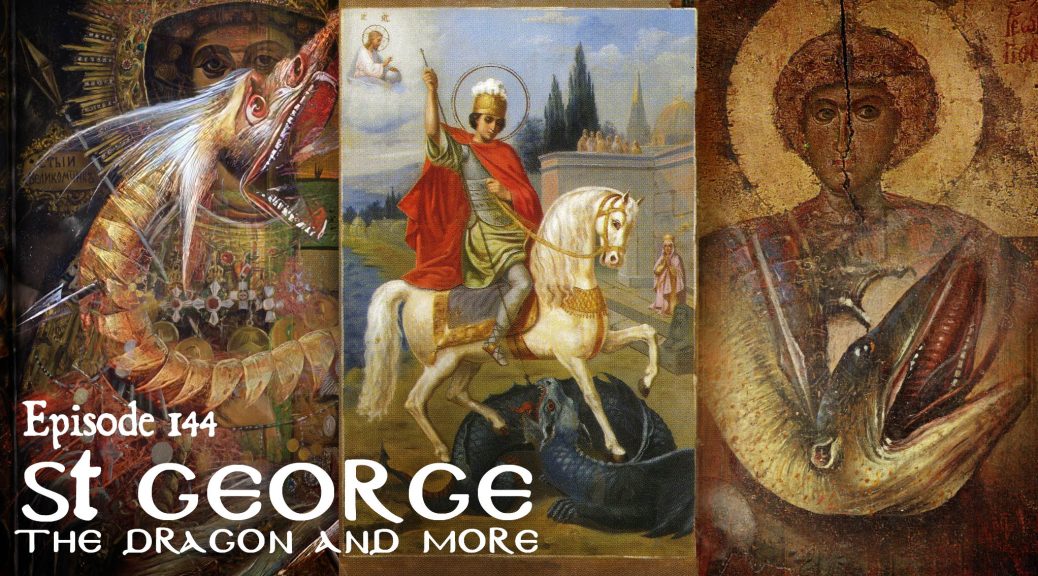

There’s so much more to the figure of St. George than his battle with a dragon. Legends also tell of his grisly martyrdom, capture of a demon, and postmortem abilities to cure madness through contact with his relics. In the Holy Land, there is even a tradition syncretizing St. George with a a supernatural figure of Muslim legend.

We begin with a look at a modernized take on the St. George legend, the annual Drachenstich, or “dragon-stabbing,” held in the Bavarian town of Furth im Wald. Beginning in 1590 with a performer representing the saint riding in a church procession, George was soon joined by a simple, canvas dragon, which over time evolved into the the world’s largest 4-legged robot used in the event today.

Mrs. Karswell next reads for us the primary source for the dragon story, Jacobus de Voragine’s collection of saint stories compiled around 1260, known as the Golden Legend. It popularized the tradition that George was a Christian soldier in in the Roman (Byzantine) army, born in Cappadocia, in central Turkey, and executed for refusing to bow to Imperial gods. There is also a princes to be rescued from the dragon but no king gives George her hand in marriage, as you might expect. Though Voragine set this episode in Libya, this setting was not really retained i the tradition.

As one of early Christianity’s “soldier saints,” George held particular appeal for soldiers of the Crusades. We hear of two incidents of George leading Crusaders to victory as recounted in the Golden Legend and the Gesta Francorum (deeds of the Franks).

When in 1483 William Caxton’s English translation of the Golden Legend appeared, anecdotes of British interest were added, including George’s connection to English knightood and The Order of the Garter. Elizabethan writer Richard Johnson featured George in his 1596 volume, Seven Champions of Christendom, elements of which were borrowed into mummers plays in which George became a hero. We hear snippets of these.

Returning to Germany, we learn how George was also said to have encouraged the armies of Friedrich Barbarossa at the Battle of Antioch during the Third Crusade. We then delve a bit more into the history of the Drachenstich performances. Some folksy details from 19th-century newspapers documenting the tradition are also provided.

We then return to the Golden Legend for an account of George’s martyrdom. The location of this episode is not specified, but George’s pagan nemesis here can be identified with Dacianus, the Roman prelate who governed Spain and Gaul. The tortures endured run the gamut from rack to hot lead, all of which are supernaturally endured until the saint is ultimately beheaded. Divine retribution in the form of fire falling from heaven is also included.

Next, we investigate earlier sources adapted into Voragine’s dragon story, the first known being an 11th-century manuscript written by Georgian monks residing in Jerusalem. George’s background as a soldier from Cappadocia is identical, as is the endangered princess, though the victory over the beast lacks elements of swordplay and is largely accomplished through prayer. In this version, George is also responsible for the founding of a church complete with healing well.

From the same manuscript, we hear a few more miracle stories, the “Coffee Boy” legend, George’s defeat of a loquacious demon, a cautionary tale of a murderous and greedy hermit ostensibly, and a charming story involving a unhappy boy, George, and a pancake.

We then take a look at the oldest St. George text probably written in Syria around the year 600. It’s known as the “Syriac Passion of St. George,” and details an extraordinary series of tortures so fantastical as to be declared heretical by the Church in the Decretum Gelasianum, probably within a century of the story’s composition.

Digging a little deeper, we then consider the Greek myth of Perseus and his rescue of the princess Andromeda, who is offered by her father as a sacrifice to a sea-monster. It’s certainly a striking parallel to the saint’s dragon legend, but the historical connections seem less profitable to trace than visual evidence found in a cave in George’s legendary homeland of Cappadocia.

There, around the town of Göreme, one can find 9th- and 10th-century “cave churches” excavated by Byzantine Christians. One site known as the “Snake Church,” is named for its murals of serpents being speared and trampled by two soldiers on horseback. One rider has been identified as St. George. The other, St. Theodore, is another 4th-century martyr and soldier-saint with parallel story elements, including calling down fire on a pagan temple and destroying a dragon. We then hear a bit more about Theodore and his connection to Constantinople and Venice. The images of George and Theodore combatting dragons, significantly pre-date the earliest manuscript narrative of George and the dragon by perhaps a century, and it’s suspected that Theodore’s killing of a dragon may be an even older story. We also hear a bit about the St. Agapetus, whose legend offers further parallels and of the Christian mystic Arsacius, of which the same could be said.

Visually, images of Christian soldier saints and dragons, such as those painted in Göreme, resemble an artistic motif of the Roman era known as the “Thracian Horseman” — representations of a mounted warrior armed with a downward pointed spear. Under his horse’s legs is usually a boar, depicted as prey. The image appears in various contexts, employed toward diverse magical purposes, which we discuss.

Also discussed is related iconography of a Byzantine (and later Carolingian) motif, “Christ in Triumph”or“Christ Trampling the Beasts,” along with images of St. George on horseback slaying a human figure believed to represent his nemesis, a pagan ruler, who in the Syriac Passion is identified as “the dragon of the Abyss.” As these predate the more literal dragon combat, an evolution from allegorical to more literal representation is suggested.

We end with stories of miracles associated with the relics of St. George, particularly chains said to have been worn by the saint in prison before his martyrdom. Preserved in a convent church in Al-Kidr, a town on the West Bank, near Bethlehem, they are said to be particularly efficacious in curing madness in those who touch them — a belief held by local Christians and Muslims alike, We also encounter the supernatural figure of Muslim legend after whom the town is named. “Al-Kidr” — translated as the Green One — who has been syncretized in local tradition with St. George.