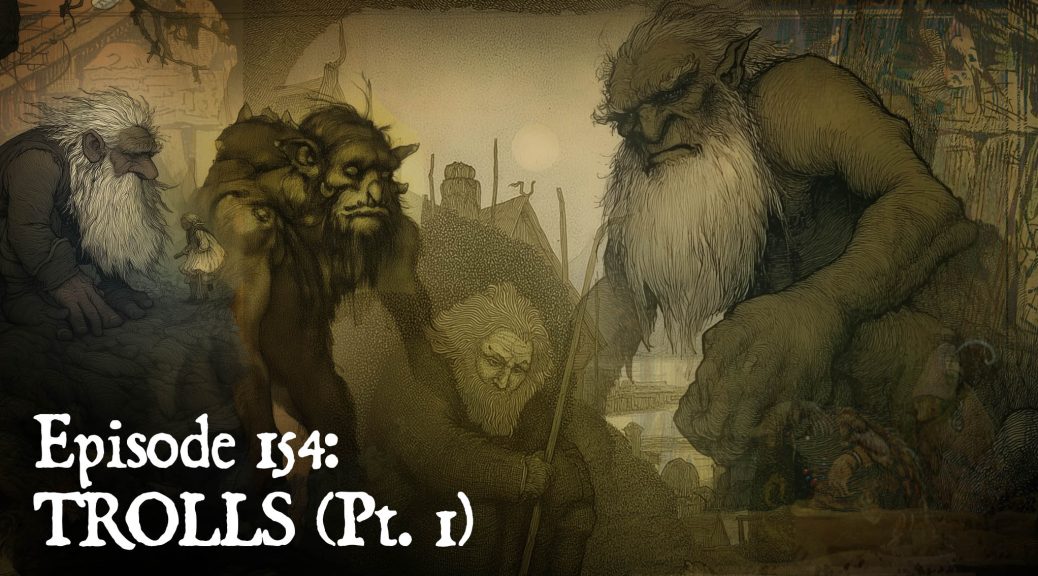

Trolls (Pt. 1)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 49:19 — 56.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

Trolls in Scandinavian folklore can be a little different from what’s imagined in the rest of the world. We begin our show with a montage of clips from recent movies, Trollhunter (2010), Troll (2022), and Troll 2 (2025) — the latter two being Netflix productions that have rekindled interest in the subject while reimagining trollsin a way that does not always conform to the folklore. While all Scandinavian countries have their share of troll lore, this episode focuses specifically on Norway, the country with the most compelling collection of troll folklore.

The first portion of our show looks at the Norwegian writer Henrik Ibsen’s play along with incidental music composed for the play by his associate Edvard Grieg. Introducing this topic is a clip from the 1970 musical Song of Norway, a fanciful Edvard Grieg biopic that garnered particularly bad reviews. We learn a bit about why Grieg hated his well-known “Hall of the Mountain King,” a composition which accompanies Peer Gynt’s encounter with trolls inside a mountain in the Dovre mountain chain. We also learn what Ibsen hoped to achieve in telling the story of his antihero Peer Gynt, and how he wrestled with the movement known in Norway as Romantic Nationalism.

Next we look at two figures integral to this movement, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, a pair of folktale collectors often described as the “Brothers Grimm of Norway.” Their 1841 publication, Norwegian Folk-Tales, along with updated volumes published in 1844, 1845, and 1871, provide most all the troll tales with examine in this episode. An exception to this is a book authored by Asbjørnsen alone, High Mountain Scenes, volume 2, Reindeer Hunt at Rondane. Published sometime before 1846, it’s the only volume referencing tales told about Peer Gynt, those being very loosely represented in Ibsen’s play.

The first of these we retell concerns a creature known as “the Bøyg,” something referred to as a type of troll in the story is described more as a giant serpent of sorts. We follow this with more Peer Gynt episodes involving male trolls flirting with human females and a troll poking his enormous nose through a cabin window and suffering the consequences inflicted by Gynt. The final story, “The Cat on the Dovre-Mountain,” takes place at Christmas, a time when troll encounters are particularly prevalent, and involves Gynt outsmarting a group of bothersome trolls via a peculiar stratagem.

Next, we run through some lesser-known details of the best-known troll tale “The Three Billygoats Gruff.” We follow this with another well-known (in Norway) story, “The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll.” It involves a youth outwitting a troll with a particularly gruesome ruse It was familiar enough to Norwegian audiences to be referenced in Trollhunter.

Next we look at a character Askeladden, who is pitted against trolls in several of Asbjørnsen & Moe’s stories. He’s usually describing the good-for-nothing youngest brother of a trio, an underdog who surprisingly achieves great things. His name (literally “ash lad”) referenes his stay-at home habits, in particular, sitting by the hearth playing in the ashes. We learn of several characters with related names and habits in Scandinavian literature and a more insultingly rude nickname for such characters, one which Asbjørnsen & Moe chose to censor from their stories.

Our next troll tale, “The Lads who Met the Trolls in the Hedale Woods,” gives us particularly monstrous trio of trolls sharing a single eyeball. While this is atypical, we also encounter here the common trope of trolls sniffing the air for “Christian blood,” a suggestion that their kind of an older pre-Christian order. A reference to trolls using magic is also contained in this story, something we’ll run into in other tales.

We then hear some clips from a couple of Asbjørnsen & Moe-inspired films, the 2017 Norwegian film Ash Lad: In the Hall of the Mountain King and its 2019 follow-up, The Ash Lad: In Search of the Golden Castle. The “Golden Castle” in Norwegian film title and the title of the relevant Asbjørnsen & Moe story is “Soria Moria Castle.” This one also features trolls, but in a peripheral role. It’s a longer legend quest rather than a short folk tale in which we encounter three multi-headed trolls holding human women captive in three different castles.

Our last story, “The Hen is Trips in the Mountain,” takes its weird title from a strange phrase uttered to open a door into a mountain, like “Open Sesame.” When a young woman enters theis particular mountain looking for a lost hen, she meets an unpleasant end, as does her younger sister, but when the youngest of the three enters, she manages not to repeat the mistakes of her two siblings and later discovers that trolls can explode when touched by the first rays of dawn (as well as turning to stone, another common folklore trope).

We wrap up the show with some interesting stats regarding the fascination trolls exert over the heavy metal subculture.