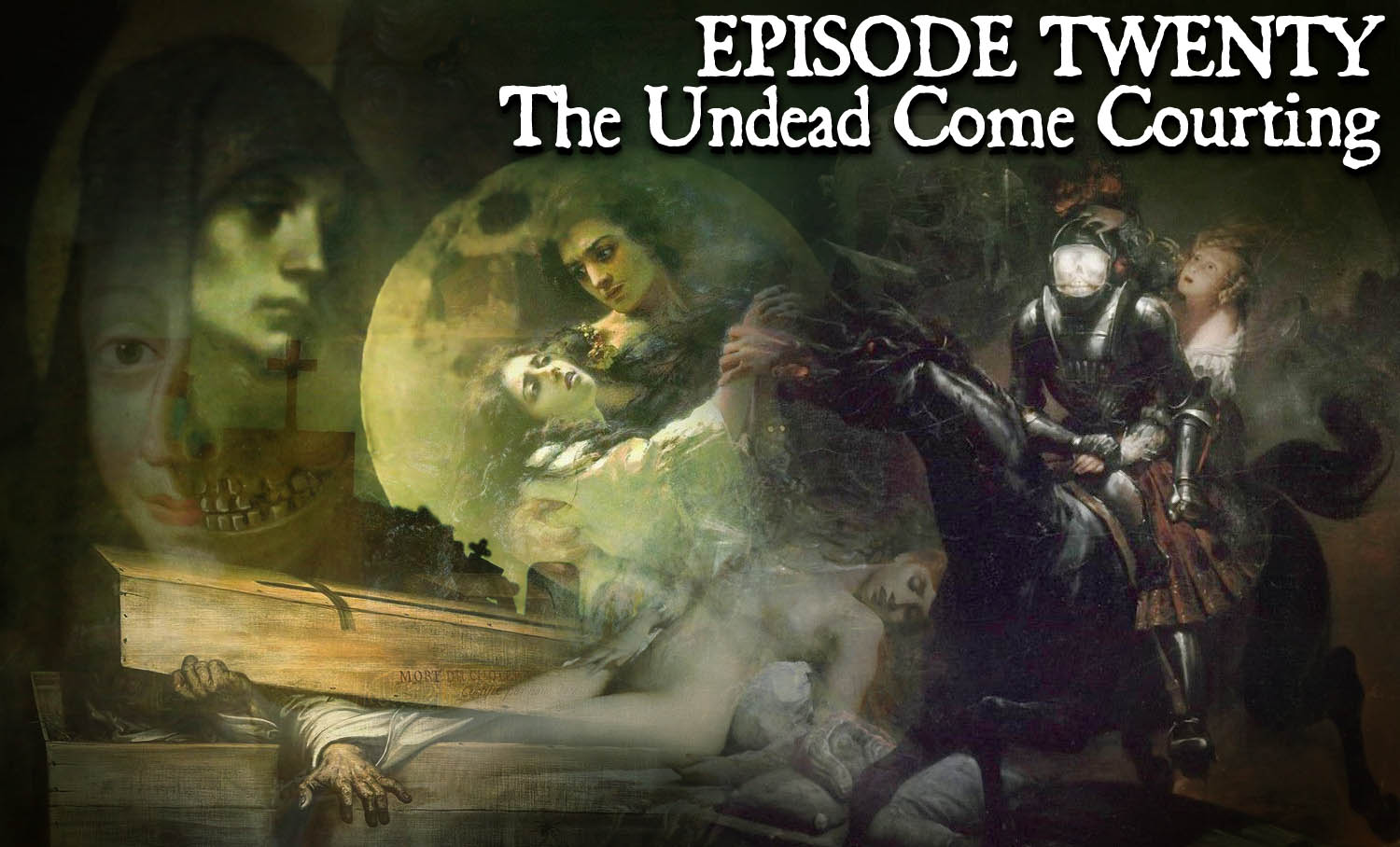

#20 The Undead Come Courting

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 42:36 — 39.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

Vampire mythology first appears in the West in works as early Romantic authors meld themes from folk ballads of resurrected lovers with Balkan folklore of the undead.

Valentine’s Day seemed a fitting occasion for this show’s look at the vampire’s tragically romantic tendency to prey upon those they love.

We begin with a (very seasonal) snippet of one of Ophelia’s “mad songs” from Hamlet, “Tomorrow is St. Valentine’s Day.” The song speaks of a lover’s clandestine nocturnal visit to a partner’s bedchamber. It represents a class of folk song called “night visit ballads.” A more ghoulish subset of these deals with lovers who happen to be dead, or undead actually.

We hear two sample songs of revenant lovers from the 16th-17th century: “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” (referencing “cold corpsey lips”) and “The Suffolk Miracle,” which bears comparison to the German poem “Lenore,” much beloved by the Romantics and Gothics, and mentioned in Dracula as discussed in Episode One.

Next we discuss the “Vampire Panic” that took place in Serbia in the 1720s-30s. We hear of Petar Blagojević, who was said to have been exhumed and found incorrupt with fresh blood at his mouth and flowing from his heart once properly staked. We hear of a similar case involving the foot soldier Arnold Paole, whose staking produced more disturbing results and whose alleged vampiric deeds led to two distinct waves of panic.

We learn how these reports were assimilated by the literary world, with an early example being German poet Heinrich August Ossenfelder’s 1734 poem “Der Vampir.” Then we look at a more nuanced suggestion of vampirism in Goethe’s “The Bride of Corinth,” a poem based on a classical account of revenant lovemaking, the story of Machates and the undead Philinnion.

Next we have a look at two other important early uses of the vampire motif in literature — two Orientalist poems — Thalaba by Robert Southey and Lord Byron’s The Giaour. Both reference Balkan folklore and superstition, and footnotes to Southey’s work include a lengthy narrative of an absurd and gruesome vampire panic on the Greek island of Mykonos in 1701. Wilkinson reads prettily from this account. Along the way, we have a look at Greek vampires in Val Lewton’s moody 1945 film Isle of the Dead starring Boris Karloff.

Byron’s contribution to Gothic literature (as host to Mary Shelley during her early writing of Frankenstein) is illustrated with another snippet from Ken Russel’s cinematic work, his 1986 film Gothic. More central to our theme, however, is The Vamyre by John Polidori, Byron’s personal physician who also shared in the evenings of ghost stories that inspired Shelley.

Byron’s contribution to Gothic literature (as host to Mary Shelley during her early writing of Frankenstein) is illustrated with another snippet from Ken Russel’s cinematic work, his 1986 film Gothic. More central to our theme, however, is The Vamyre by John Polidori, Byron’s personal physician who also shared in the evenings of ghost stories that inspired Shelley.

We learn how The Vampyre grew out of Byron’s The Giaour, of the influence its vampiric character exerted on Stoker’s Dracula, and of the unlikely spin-offs the story generated.

Then we have a look at Tolstoy’s lesset known 1839 vampire novella The Family of the Vourdalak and its treatment in Mario Bava’s 1963 horror anthology Black Sabbath, also featuring Boris Karloff.

Tolstoy’s story also happens to be set in Serbia, bringing us back to the country’s long history of vampirism, the famous Serbian Vampire Sava Savanović, and the bizaare 1973 Yugoslavian film featuring Savanović, Leptirica.

We close with a strange story of the the Serbian undead from the year 2012. A musical setting is provided.