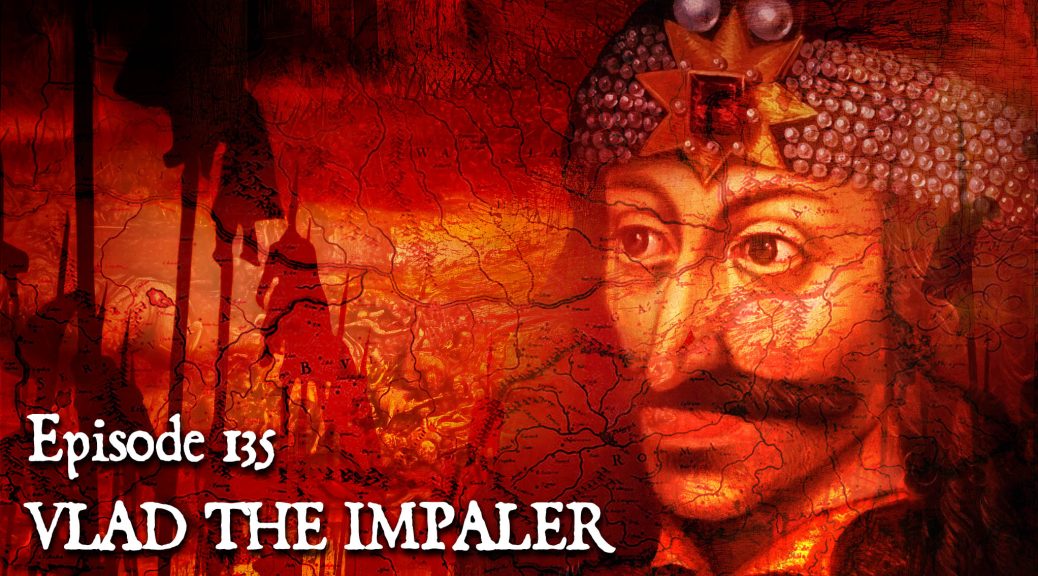

Vlad the Impaler

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 54:42 — 62.6MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

A figure of mythic proportions during his lifetime, Vlad the Impaler’s notoriety receded over the centuries only to be resurrected in the 1970s, when a pair of Boston University scholars went public with theories connecting him to Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula.

We begin with snippet of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the first film to connect the literary vampire with the Eastern European prince — a rather ironic departure from Stoker’s novel, which references the historic figure only in passing.

Vlad’s 15th-century notoriety was sparked by two German texts both published around 1463, or shortly thereafter. Probably the earliest of these,written anonymously and published in Vienna, was titled, The History of Voivode Dracula, is sometimes called “the St. Gallen manuscript” named for the Swiss city where it is preserved. (“Voivode,” is a Slavic term, used in this context to mean, essentially, “Prince.”) The second is a rhymed narrative written by Michel Beheim, a poet associated with the Meistersinger tradition and a performer at the court of the King Friedrich III. About three decades later, in 1490, Vlad’s story appeared in northwestern Russia. We don’t know its author but the monk who copied it from a lost original, mentions that his source was written in 1486.

All three of these narratives provide plenty of gruesome anecdotes detailing the voivode’s cruelties. Before going further into Vlad’s history, and as a quick appetizer, Mrs. Karswell reads a description by Beheim of a ghastly picnic said to have been enjoyed by the voivode.

Next, we clear away some misconceptions regarding Vlad the Impaler, the first having to do with his name. Called “Vlad Țepeș” (Vlad the Impaler) in Romanian, he is less dramatically referred to as Vlad III. His father, Vlad II, was also known as “Vlad Dracul.” His son, using the Slavonic possessive form of that was referred to as Vlad Drăculea (that is, “of – the son of – Vlad Dracul). The father’s epitaph means “Vlad the Dragon,” referencing Vlad II’s (and later Vlad III’s) membership in The Order of the Dragon, a society of Christian knights dedicated to staving off incursions of the Muslim Turks into Christendom.

We then have a look at Vlad III’s over-emphasized association with Transylvania, one of the three historical regions (along with Moldavia and Wallachia) that would later become Romania. In fact, it was not Transylvania but Wallachia over which both Vlad II and Vlad III served as voivodes. While Transylvania was his birthplace, at the age of 4, he and his family departed for Wallachia, and Vlad’s historical relationship with Transylvania was later anything but friendly.

We then look at Wallachia’s role as a buffer between Ottoman regions to the south and Hungarian/German controlled regions to the north, as well as the regrettable deal Vlad II made with the Turks to keep the peace.

The last involved the “child levy,” or “blood tax” demanded by Sultan Murad II. Known in Turkish as “devshirme,” this was a sort of ransom imposed on Vlad II, requiring that he leave his sons Vlad and Radu with the Turkish court to ensure the ruler’s compliance with the sultan’s demands. We hear some interesting details on this four-year exile, some of which likely shaped Vlad III’s actions later in life.

Before Vlad III is released, his father and eldst brother Mirea are murdered by Hungarian forces, who install their desired ruler on the Wallachian throne. While Vlad III manages to briefly seize his father’s throne while the Hungarians are distracted in conflicts with the Turks, he’s again forced into exile after only serving one month.

After several year in exile among the Ottomans and Moldavians, Dracula takes advantage of the death of the Hungarian ruler, János Hunyadi, to again sieze the Wallachian throne, and it’s during this second reign that he gains his notoriety. The first order of importance is to punish Transylvanians who aided the Hungarians responsible for his father and brother’s deaths. Beheim provides some gratuitously gruesome descriptions of exotic acts of revenge.

We then hear of Vlad III’s murder of Turkish emissaries, and of the campaign Sultan Mehmet II mounts to punish the Wallachians. Vasly outnumbered by the Turkish forces, Vlad and his men resort to guerrilla warfare to slow down the Ottoman army advancing on his capital city of Târgovişte.

On the night of June 17, 1462, Wallachian troops under Vlad conduct an attack on the sleeping Ottoman camp, in an assult known by Romanians as the “The Night Battle” or “Battle with Torches.” The actual tactical gains made during this foray are debated, but the following day, the Ottomans are subjected to a powerful psychological assault as they encounter a forest of their comrades collected from the battlefield and impaled on stakes. According to the Greek historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles, roughly 20,000 corpses were seen spitted in a field measuring two miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide.

After this, we hear of Dracula’s 14-year imprisonment by the Hungarians, during which he supposedly amused himself by impaling rats in his cell. We then hear of the voivode’s death at the hands of his own men in 1476, and decapitation by the Turks.

The literary embellishments of some of our German texts, and the rationale for such, are next discussed and these are contrasted with stories from the Russian collection that offer a slightly more balanced picture of the ruler, portraying him through several anecdotes as one who maintains social order through highly effective (if brutally excessive) means.

We then take up the question of whether, or to what extent, Bram Stoker based his vampire on Vlad III, finding but a few points of agreement as well as details (largely geographic) arguing against the idea.

Last, we have a look at Vlad the Impaler’s rediscovery via the 1972 book, In Search of Dracula, by Romanian émigré Radu Florescu and Raymond T. McNally, a scholar of Russian and Eastern European history. Mr. Ridenour offers some sour grapes on the success of this bestseller and ends the show with a clip featuring Christopher Lee from a 1975 same-name documentary inspired by the Florescu-McNally book