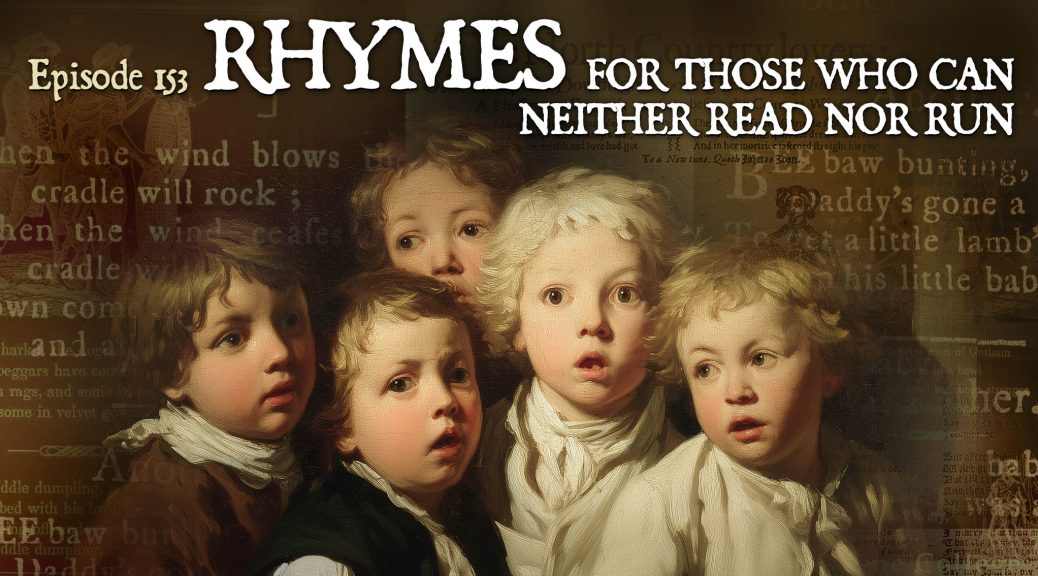

Rhymes for Those Who Can Neither Read Nor Run

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 37:06 — 42.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

Gammer Gurton’s Garland, published in 1784, is one of the earliest collections of English nursery rhymes, and contains verses both familiar and alarmingly unsettling.

Intended to be read to toddlers (i.e., “children who can neither read nor run,” according to its subtitle) and named after a fictitious Grandma (“Gammer”) Gurton, who’d be analogous to Mother Goose, the volume were assembled by the eccentric scholar Joseph Ritson, who was known for his collecting of Robin Hood ballads, vegetarianism and ultimate descent into madness.

We begin our episode with a snippet of a 1940s’ rendition of “Froggy Went a-Courting” by cowboy singer Tex Ritter. It’s a relatively modern take on Ritson’s “The Frog and the Mouse.” But like quite a few rhymes in the collection, this one had appeared in print earlier. Already in 1611, British composer of rounds and collector of ballads, Thomas Ravenscroft, had written out both lyrics and musical notation for “The Marriage of the Frogge and the Mouse,” a song he described as a folk song or “country pastime.”

While a few other rhymes in Ritson’s collection were borrowed from one of two earlier editions of nursery verses (both published as Tommy Thumb’s Song Book 40 years earlier), most of what he collected appeared for tge first time in Gammer Gurton’s.

We hear a bit about some of the familiar rhymes that premiered in this collection, including Goosey, Goosey Gander, Ride a Cock-Horse to Banbury Cross (with the “rings on her fingers and bells on her toes” lady), Bye, Baby Bunting, and There Was an Old Woman who Lived in a Shoe.” Ritson’s version of the last, however, takes a rather rude and unexpected turn.

Many, if not most, of Ritson’s rhymes seem to have been weeded out of the gentile or sentimental collections we know today. Naturally, we devote attention particularly to these objectionable verses. Included are a handful of aggressively nonsensical rhymes, which could pass for 18th-century Dada and verses notable for their cruelty. The most alarming contain brutal slurs, threats, and playful references to assault, adultery, matricide, suicide, and animals going to the gallows.

The last third of our episode is dedicated to poems noteworthy for their survival as musical ballads. The first discussed is the basis for song “Lady Alice,” which later appears in James Child’s 1860 collection The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Ritson’s version, “Giles Collins and Proud Lady Anna,” is a greatly simplified version of the ballad later cited by Child. While toddlers might appreciate the simpler storytelling, the subject matter — namely, doomed lovers — is not the normal stuff of healthy nursery rhymes. More surprising, is the fact that Ritson’s story begins with Giles Collins in the process of dying and Lady Anna dead (of heartbreak) within a few verses. After their deaths, a tentative suggestion of undying love, a lily reaching from Giles’ grave toward Anna’s, is destroyed – an unhappy turn on the not uncommon motif of a rose and briar entwining over lovers’ graves.

We close with a discussion of “The Gay Lady who Went to Church,” an innocuous-sounding rhyme, intertwined with the history of two rather gruesome folk songs popular around Halloween: “There Was an Old Lady All Skin and Bones” and “The Hearse Song” AKA “The Worms Crawl In.” Also discussed is a surprising link between Ritson’s nursery rhyme and a faux-historical ballad invented for the very first Gothic novel, Matthew Gregory Lewis’ The Monk.

INFORMATION RE. THE FOLK-HORROR GIVEAWAY DISCUSSED IN THE SHOW OPEN CAN BE FOUND HERE: https://www.boneandsickle.com/giveaway/