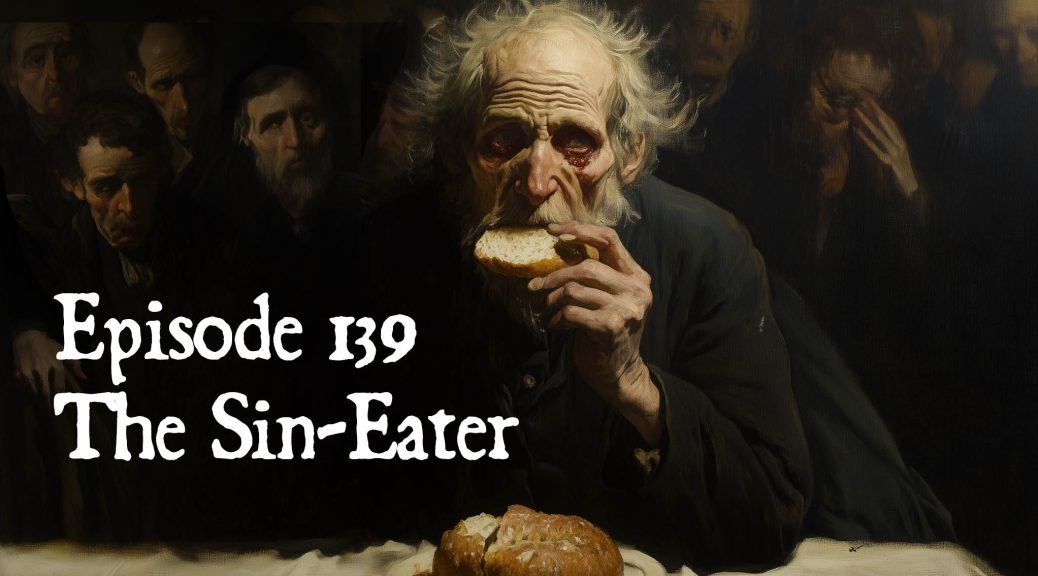

The Sin-Eater

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 45:20 — 51.9MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | RSS | More

The Sin-Eater was a figure associated with funerals of the 17th – 19th century, mostly in Wales, and the English counties along the Welsh border. According to tradition, he was invited by grieving families to transfer the burden of sins from the deceased to himself by consuming bread and beer in the vicinity of the corpse, after which he might receive some financial compensation. He typically came from the fringes of society and was said to be motivated by a combination of poverty, greed, and irreligious indifference to matters of eternal judgement.

After a quick montage of clips from the generally terrible films made on the theme —Sin Eater (2022), Curse of the Sin Eater (2024), The Last Sin Eater (2007) — we review the historical references to the tradition, which are surprisingly few in number.

The first comes from a particularly early 1686 collection of British folklore written by John Aubrey, The Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme. His characterization of the custom is essentially that described above and despite the early date of the text, he describes the practice using the past tense, though qualifies this somewhat later mentioning that it is “rarely used in our days.” Mrs. Karswell, of course, reads Aubrey’s original text along with our subsequent examples.

Our next account from 1715 comes from antiquarian John Bagford (published later, in 1776) in John Lelan’s, compendium, Collectanea. It does not mention Wales but locates the custom in Shropshire, an English county bordering Wales. It also has the Sin-Eater remaining outside the house where the body lies as he consumes his bread and ale. Bagford also adds a verbal formula, which the Sin-Eater is supposed to pronounce, mentioning the deceased’s soul attaning “ease and rest,” for which the Sin-Eater’s soul has been “pawned.” These phrases are recycled in later literature on the topic.

The next text comes from 1838, appearing in the travelogue Hill And Valley: Or Hours In England And Wales by the Scottish novelist, Catherine Sinclair. It’s particularly brief, adding little detail other than specifying the tradition as one (formerly) belonging to Monmouthshire, in eastern Wales. She also characterizes the custom derisively as “popish,” or belonging to the Catholic past.

The next and final account (not counting clearly recycled retellings of those above) was contributed by Matthew Moggridge in an 1838 journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. It also relegates the tradition to the past, placing it specifically in the Welsh town of f Llandybie. Moggridge removes the ale, keeps the bread, and

adds salt (used symbolically rather eaten). He also makes explicit the Sin-Eater’s pariah status.

Aubrey’s, Bagford’s, an Moggridge’s accounts received greater attention when collected in an 1892 article by E. Sidney Hartland in the journal Folk-Lore, the publication of the British Folk-Lore Society. Hartland’s “rediscovery” of these texts fueled the interest of the British public and corresponded with a rising fascination in such things as represented in the arts by the Celtic Revival instigated by William Butler Yeats’ 1893 work, The Celtic Twilight and the ongoing publication between 1890 and 1915 of James Frazer’s evolving work on folklore, The Golden Bough.

As there are no firsthand accounts describing sin-eating as a custom still in existence a misinterpretation or garbled accounting of another tradition may lie behind the concept of the Sin-Eater. The second half of our show examines the extent to which creative myth-making formed the concept along with the role older Catholic practices may have contributed to the tales.

The earliest literary Sin-Eater we encounter appears in a chapter of Joseph Downes’ 1836 novel, The Mountain Decameron. Mrs. Karswell reads an evocative passage or two describing a traveler stumbling into a scene of sin-eating while traveling through a haunted bog. Along with several other quick summaries of post-Hartland novels treating the topic, we hear a sin-eater clip from a BBC adaptation of Mary Webb’s 1924 novel, Precious Bane and learn how Christanna Brand’s 1939 short story “The Sins of the Fathers,” ended up in an episode of Rod Serling’s 1970s TV series, Night Gallery.

We then survey a number of transactional funeral customs possibly reinterpreted as Sin-Eater lore, among these: “funeral doles” and “avral feasts” at which property of the deceased was disbursed, unsavory pallbearers paid off in food and drink, and the distribution of “soul-cakes “and the custom of “souling” to assure the deceased’s heavenward ascent. Best of all, we learn about that cousin to the soul-cake — the funeral cookie.