The Hellish Harlequin: Phantom Hordes to Father Christmas

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 47:31 — 43.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Podchaser | Email | RSS | More

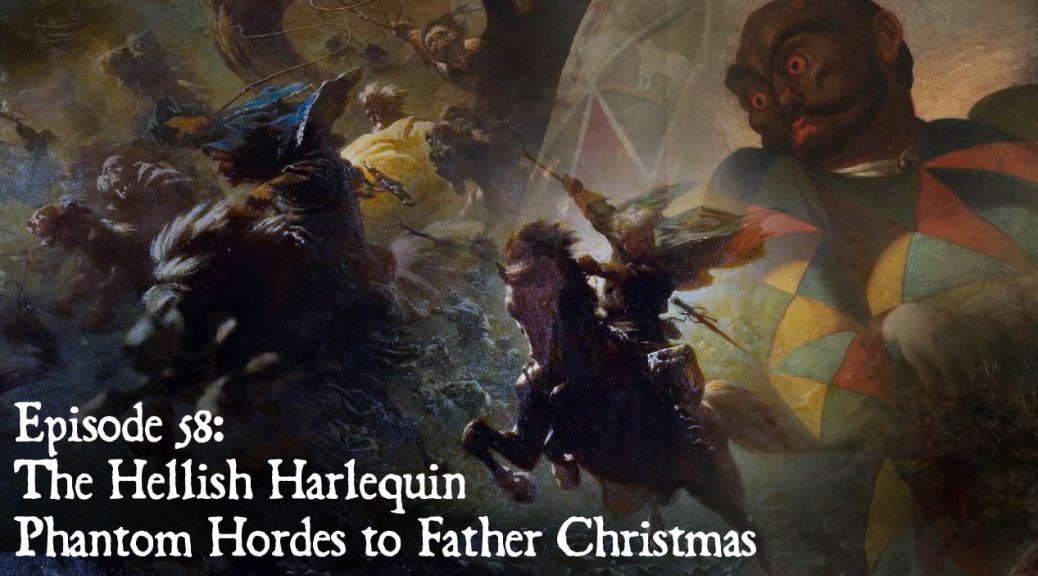

Harlequin is an enigmatic figure with roots in dark folklore of France, specifically that of the Wild Hunt (Chasse Sauvage) a nocturnal procession of ghosts or devils, particularly associated with the time around Christmas and New Year. The myth is also common to England and examined more closely in its Germanic manifestation in Episode 16, “The Haunted Season.” We open with a snippet from an album dedicated to Hellequin’s folkore by a Belgian band called Maisnée d’Hellequin.

In the show, we trace a thread leading from medieval stories of Hellequin (Harleqin’s ancestor in France) and King Herla (the English equivalent) to the more recent theatrical figure of Harlequin, along the way examining a link with the traditional English Christmas play (mummers’ play) and its role in the evolution of the figure of Father Christmas.

Our first story comes from the French-Norman monk Oderic Vitalis, from volume two of his Ecclesiastical History. It was written in about 1140, making it not only the first account mentioning Hellequin (“Herlequin” in his text) but also the first European ghost story, one Vitalis relates as a true event transpiring on New Year’s Eve 1091, and told to him by an eyewitness, a priest, by the name of Vauquilin (Walkelin).

While returning from a visit to an ailing member of his parish, Vauquilin, hears the thunder of what sounds like an approaching army and is met by a giant with a club, whom he recognizes as Hellequin and who in this case serves as a sort of herald of the ghostly crew that follows. It’s a richly detailed and extravagantly ghoulish tale, splendidly read by our own Mrs. Karswell.

Without giving away too much, suffice it to say, that the spirits Vauquilin sees passing are enduring a sort of purgatorial torment for past sins, an apparently temporary but unenviable state of earthbound damnation. (For more on medival tales of ghosts visiting mortals from purgatory, see our “Ghosts from Purgatory” episode.) In the procession, these sinners are accompanied by devils who torture them, chief among these, apparently Hellequin.

Our next story, from around 1190 paints a more detailed picture of the English version of Hellequin, King Herla. It was written in Wales by the courtier Walter Map and contained in his eccentric collection of myths and pseudo-historical anecdotes called De Nugis Curialium, or “trifles for the court.” This one’s more of an origin story explaining King Herla’s transition from mortal king to ghostly rider. I won’t give away the details on this one either, but it involves a dwarf king’s wedding party inside a mountain, parting gifts, and bad gift etiquette.

Our third story comes from 14th-century France and is a bit different as it doesn’t describe what are supposed to be supernatural events but a representation of this, a fictional procession imitating Hellequin’s ride.

The procession in this text takes the form of a charivari, a sort of parade with participants noisily banging pots and pans or playing discordant music on various instruments. Charivaris were most commonly occasioned by weddings, in particular those which defied some social convention, such as the rushed wedding of a widow or widower who not honoring a suitable period of mourning.

In our story, the wedding is that of a figure named Fauvel, who is marrying the allegorical figure of Vainglory. Fauvel, by the way, is a horse representing all the worst traits of social climbers of the day.

The satiric Romance of Fauvel (“Romance” = “novel”) was written in 1316 by a Gervais du Bus, then much enlarged in 1316 with additions, including our charivari scene, by another writer by the name of de Pesstain. The text describes a particularly carnivalesque scene including a bizarre, wheeled noise-making machine, and all sorts of taboo-breaking behavior by the participants. The connection between the Wild Hunt and carnival is also noted in an 18th-century German carnival procession we hear described, one mimicking in this case Frau Holde and her retinue. The Fauvel passage ends with the narrator encountering a giant recognized as Hellequin, who is bringing up the rear — leading from behind in this case.

We then have a look at the theatrical, Harlequin who originated in the 16th century as a stock figure from the Italian commedia della’arte, where he’s known as Arlecchino. He wears a black half-mask along with a suit sewn with multicolored diamonds. And he always carries a sort of short club, an element that seems to be borrowed from the diabolical Hellequin. Though he’s most well known as an Italian figure, Arlecchino seems to have his source, as a theatrical entity, in a devil of this name from medieval French mystery plays. We also look at some supernatural Hellquins in secular plays including a 13th-century work by the Norman poet Bourdet and the satiric work, Le Jeu de la feuillée by Adam de la Halle.

We then follow the theatrical Harlequin to England where in the 18th century, the commedia plays morphed into were called “harliquinades,” frothy comedies, which eventually evolved into the British tradition of Christmas pantos/pantomimes.

We also examine a little remarked upon influence of the commedia and harliquinades on England’s seasonal mummer’s plays, particularly the traditional Christmas Play. An echo of Arlecchino’s trademark slapstick, or club, along with a mumming character called “Father Beelzebub” helps us connect the character of Father Christmas found in these plays with the devilish old Hellequin/Herla of French and Anglo-Norman folklore.